Ahmad Jamal and Me...

We had to send for them mail order. I did all my collecting in my formative years, which would have been in the ’40s and ’50s. I was real eclectic. Georgie Auld and Boyd Raeburn recordings with Erroll Garner. Savoy records with Don Byas. Those early things Martial Solal did for Contemporary. The old Comet 12-inch masters with Art Tatum and Tiny Grimes and Slam Stewart, and Nat [Cole], and Lester Young playing‘Body and Soul.’ Lucky Thompson, all that kind of stuff,

Ahmad Jamal crate digging, circa 1940s

That’s a unique thing about people in American Classical Music, which is a phrase I coined some time ago: you have to know the best of both worlds. I was playing Franz Liszt in competition when I was ten years old, but I was also playing Duke Ellington. So that’s a marvelous thing about the wonderful players that make up our genre. We have to be multi-dimensional. Dave Brubeck has to know Mozart. He has to know Duke Ellington, and it’s the same way with George Shearing; he can play the concertos but he can also write “Lullaby of Birdland.” So that’s the wonderful thing about people that are working in our field. They’re multi-dimensional; they’re not one-dimensional. That’s why I call them “American Classicists.” I think that “jazz” does not define properly what we do. I’m not paranoid about the term “jazz” but I don’t call myself a “jazz musician.” I call myself and my colleagues, the John Coltranes, and the Duke Ellingtons, “American Classicists."

Ahmad Jamal, interview 2011

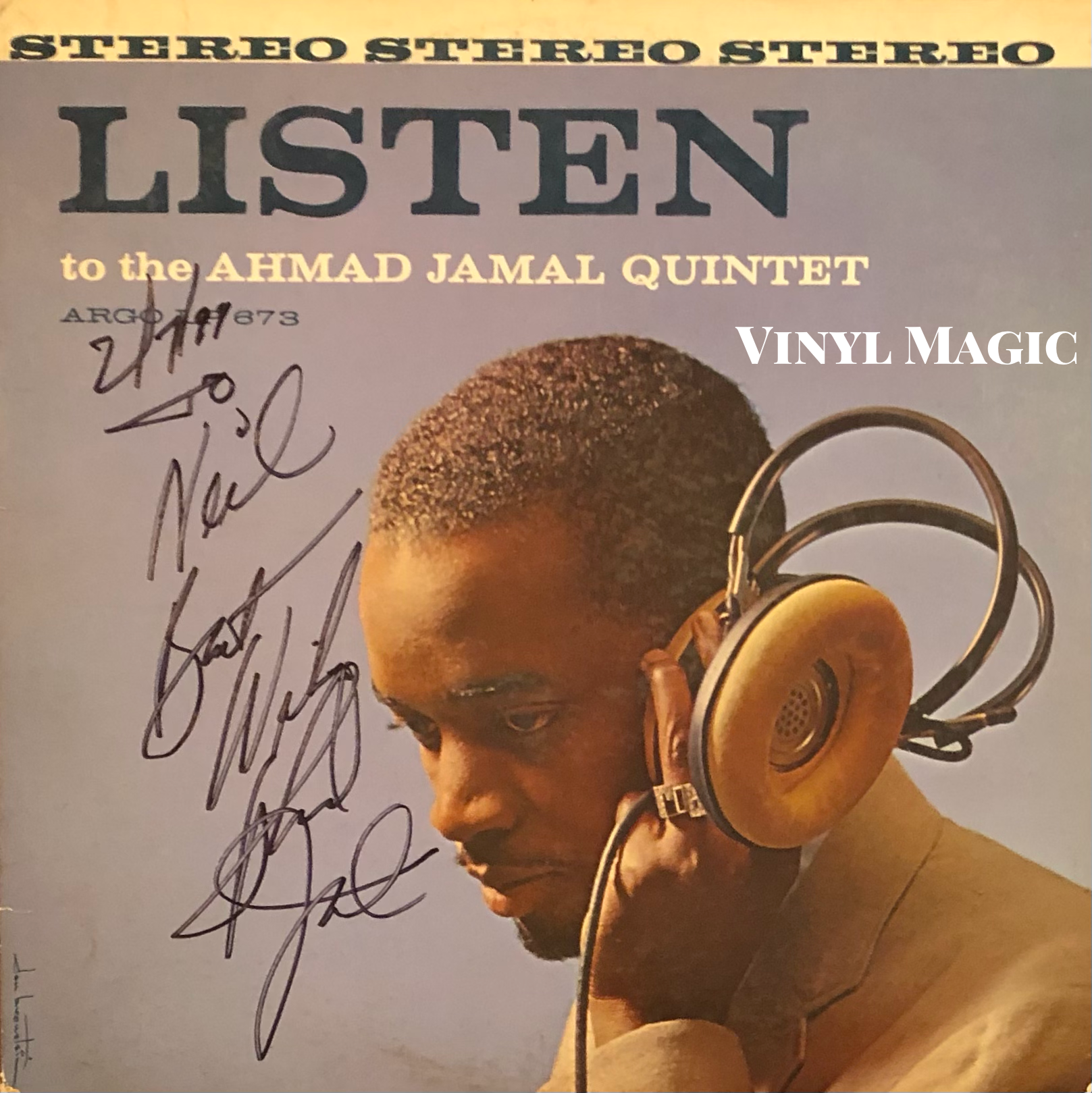

Happy Moods (1960) signed by Ahmad

He knocked me out with his concept of space, his lightness of touch, and the way he phrases notes and chords and passages. When people say Jamal influenced me a lot, they’re right…

Miles Davis

I always write first and the composition dictates itself to me. I write the music and to me, the music dictates the title. The dynamics are important, the research is important, the melodic line of the song is important. Everything is important with music. It is always a challenge. Music is a constant challenge. You are not ever finished. People ask me what my favorite record is and I say that it is the next one. That is about the size of it. I am always looking forward to the next go around because I always am learning something during the process of recording and when it comes out, I am faced with more challenges, happily so. I had several ideas and the main idea was to record a wealth of tracks, which I find is very necessary. It is much better to have more than not enough...as was the case with my model release, At the Pershing, which is really a historic piece of recording or historic musical document. I had forty-three tracks when I went into the studio. I only used eight. I always had the concept of recording a wealth of tracks because you have got to have choices. When you don't have enough choices, you run into trouble and so I always had a concept of recording enough so I can have some good selections.

Ahmad Jamal, interview 2003

I’m trying to figure out what the black and white keys do after eighty-six years! I first sat down at the piano when I was three years old, and I’m still trying to figure out what they do! I learn something new every time I sit down. I sat down early this morning, because what I like to do is get to the piano first. I finally learned that, because if I don’t, all this other mess — computers and this and that and Facebook and other junk — it drains you. So I have nothing left for the piano, especially at eighty-nine years old!

Ahmad Jamal, 2019 interview

Ahmad Jamal’s Alhambra (1961) signed by Ahmad

Ahmad Jamal and Me…

The great Ahmad Jamal left the bandstand on April 16, 2023, He was ninety-two. Marvelously inventive and influential, Ahmad released over fifty records as a leader during his seven decade-plus career, and he was a hero to pianists Bill Evans, Herbie Hancock, Keith Jarrett and McCoy Tyner who cite him as a seminal influence, but also to musicians of every stripe and discipline. As Miles Davis once stated, "All my inspiration comes from Ahmad Jamal," and it wasn't hyperbole. Miles' early repertoire was eerily similar and seemingly cribbed from Ahmad's setlist: "Ahmad's Blues," "Autumn Leaves," "A Gal In Calico," "New Rhumba," and "Surrey With The Fringe On Top" were some of the songs that Miles played and recorded with his band after hearing Ahmad's expert interpretations. It didn't stop there. Miles even sent his pianist Red Garland to check out his gigs to help him learn and assimilate Ahmad's techniques.

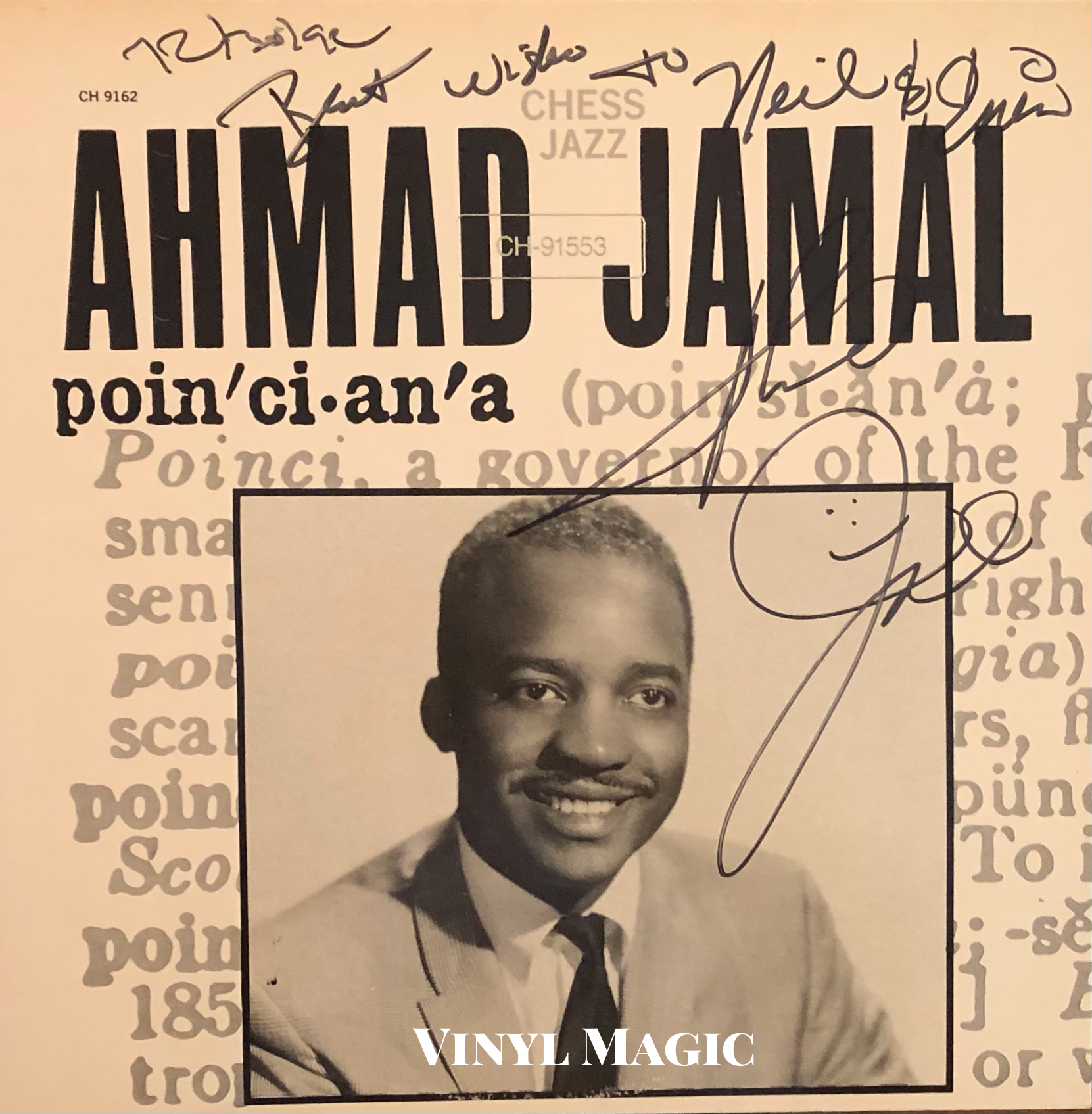

Poinciana (1963) signed by Ahmad

Ahmad was born Fredrick Russell “Fritz” Jones in 1930 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Awash in the vibrant Steel City jazz scene, Ahmad was surrounded by gifted pianists and musicians Earl 'Fatha' Hines, Mary Lou Williams, and Errol Garner, "my major, major influence." Starting at age three at the behest of an uncle who encouraged Ahmad to mimic him, a lifelong love affair with the piano and composing began, "Music chose me. I didn't choose it. I was playing at three years old. When you are that young, you don't make choices. Choices are made for you. The instrument was in my mother's house. It was already there, so I passed by it one day and sat down. The rest is history." And what a fabulous history and legacy it is.

Live At The Pershing: But Not For Me (1958) signed by Ahmad

Ahmad’s skills were honed in the American Federation of Musicians’ local 471 Musician's Hall which was a thriving hub for visiting musicians and local stars like bassist profundo Ray Brown, guitarist George Benson, saxophonist Stanley Turrentine, among other Pittsburgh denizens. Ahmad was only fourteen but he was warmly embraced, "I was playing with Honey Boy Minor and guys sixty years old when I was eleven, because I knew the repertoire. We had the musicians union. The union had a minimum age, and I joined the union when I was fourteen. I escalated my age, and the president...he knew I wasn't sixteen." It didn't make any difference to the members. If you had the chops to perform, you were welcome, and Ahmad was most welcome. Upon graduation from Westinghouse High School, Ahmad toured with the George Hudson Orchestra and performed in nightclubs as a sideman. Ahmad had hopes of attending Juilliard School of Music in New York City but the opportunities for an African American pianist in those days were scant and fleeting, so he concentrated on gigs, “It was 25 cents here, $6 there. When I got up to $60 a week, which was as much as my father was making, I said, well, this is it.” The road beckoned and Ahmad accepted the challenge.

The Awakening (1970) signed by Ahmad, Jamil Nasser

Born a Baptist, he converted to Islam while on the road in Detroit and changed his name to Ahmad Jamal. He was attracted to the religion because “Our motto is 'Love for all; hatred for none.’ Whenever I veer off the straight-and-narrow, that's when I make my mistakes, and I've made a lot of them in my life, believe me." In a 1959 Time Magazine article he also explained, “I accepted Islam because it took me from darkness into light and gave me direction...When my people were brought over here from Asia and Africa, they were given various names, such as Jones and Smith, I haven't adopted a name. It's a part of my ancestral background and heritage: I have re-established my original name. I have gone back to my own vine and fig tree."

Digital Works (1985) signed by Ahmad, Happy New Year

His delicate touch, phrasing and sense of space was emulated by many, and hip hop artists Common, Jay-Z, J Dilla, Nas, and De La Soul also sampled his works in some of their recent songs. In fact, over two hundred-seventy tracks from hip hop artists have used Ahmad’s glorious riffs. Ahmad could also turn pop ephemera like the "Theme From MASH" into a jazz tour de force with his florid and virtuoso playing. A 2012 studio release, Blue Moon showcased Ahmad's skills as he re-invented the title track (a 1934 Richard Rodgers show tune) into a marvelously, percolating ten minute Latin percussive burner. "Blue Moon" never sounded fresher or better than in his eighty-two years young hands!

Digital Works (1985) signed by Ahmad, “To Just Sign It family”

Erin and I were fortunate to see Ahmad many times and he always put on a great show. For fifteen-plus years, he did a New Year's Eve show at Blues Alley in Washington, DC which was a highlight of the holiday season. He was always kind and gracious when we met him and he signed a bunch of albums over the years. He personalized each album to me, my wife, my kids, whomever. After going through a stack in 1999 at the Iridium Jazz Club, when he got to Digital Works (a copy which he had signed "Happy New Year" at Blues Alley many years earlier), I told him he could just sign it. He smiled, scribbled away, and handed it back. The inscription read, "To: 'Just Sign It' family, Ahmad Jamal".

All Of You (1961) signed by Ahmad

Harold Mabern, the great Memphis jazz pianist once observed, “The space that Ahmad leaves in his playing creates a tension that captivates his audience....I tried to practice a trill that he makes look so easy, but I gave up." And as the great Thelonious Monk reminds us, "What you don't play can be more important than what you do.”

Macanudo (1963) signed by Ahmad

Ahmad Jamal, a master of time and space, he made it look so easy and sound so beautiful. His words about his unrelenting drive to create music say it best: “When I pass a piano anywhere, I have to touch it or play it, The reward of being a musician is not money. It’s the wonderful, indescribable feeling of knowing you’re performing at your highest level. It’s a spiritual feeling. You can always make money, but you can’t always latch onto your own spirit. Maybe these moments represent the ultimate freedom."

Asalamalakum Ahmad. We'll see you on the other side.

Choice Ahmad Jamal Cuts (per BKs request)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z0e2G32f3IU

“Poinciana” Live At The Pershing 1958

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FcUvkO4A5Vo

“Blue Moon” Blue Moon: The New York Session 2012

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xnW9wNN_IVg

“Autumn Leaves” live in Paris 2017

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Iboh0JPLfk

“Ahmad’s Blues” live

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aPLNWFpPQlQ&list=PL21Bp_pAILgf_cItY7ACkolXIcyNdgRLW&index=2

“I Love Music” The Awakening 1970

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ixsSkaCRaAw

“I Hear A Rhapsody” A Quiet Time 2009

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9quwLksJbNA

“The World Is A Ghetto” Ahmad Jamal’73 1973

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZCPtNRl1q0w

“Theme From MASH” Digital Works 1985

But Not For Me (Chess reissue, 1986 release) signed by Ahmad