Jackie McLean and Me…

I wanted to play alto like a tenor, because Lester Young was the person who really moved me, he and Ben Webster. Of course, now I can appreciate the alto saxophonists from the era, people like Johnny Hodges, but at that time, I couldn't use it too much. And then I heard Charlie Parker. There was no thought after that about how I wanted to play.

Jackie McLean

McLean’s Scene (1957) signed by Jackie

As far back as 1957, i’ve had moments on the bandstand when Charlie (Mingus) has roused me into going out into things I didn't know about. I turned to Charlie one night when he taught me a new tune and asked, 'What are the chord changes?' He said, "There are no chord changes." I asked, 'What key am I in?' He said, "You're not in any key." This left me in a hung-up situation, but when I got out there and played, I felt something different. But I was too hip at the time to admit it...I was too set on playing up and down chord changes. Now I can understand why musicians are taking different roads out, because personally, I get tired of playing the same keys, chord changes, and tunes over and over again. I find that when you wander away from the basic melody or the basic structure of a tune, and go out into something which has been termed "freedom", it gives you a wide span on what to play. because actually, you're creating upon your own creation. Like you may stumble on something by accident and create something from that.

Jackie McLean on playing with Mingus, Downbeat 1963

4, 5 and 6 (1956) signed by Jackie, Donald Byrd, Mal Waldron

Jackie, just for me and for so many others, just turned our whole world around...he used to call it “Man and Music,” and now he got politically correct — it’s called “People and Music” or something. He goes back to Africa and makes you realize… he gets into the origins of Man, and things that we take for granted and that you don’t get educated about in public schools generally. Maybe nowadays you do, more so than 1985. Then he takes you through the whole music of slavery and field hollers, and how that evolved into the blues and brass bands and all that kind of stuff. So by the time you get to the second semester, to Charlie Parker and what he can really first-hand tell you about him, it’s pretty exciting. It really gives you a tremendous concept for the history.

Trombonist and former student Steve Davis on Professor Jackie McLean at the Hartt School of Music

Malkin’ The Changes (1957) signed by Jackie

As far as my sound is concerned, I think that the person that influenced me the most about how to use my sound was Miles (Davis).... I used to listen to Miles on all the sideman things that he was on, even with Bird, and he would always emerge with something of his very own. You know, that haunting, kind of sitting alone in Alaska, kind of sound that Miles gets. It's a very lonely and mournful sound that he gets. And even though I can't emulate that on the alto, I can certainly parallel it in some ways. And my years that I worked with Miles, well he had a great influence on me.

Jackie McLean

A Long Drink Of The Blues (1957) signed by Jackie, Curtis Fuller, Louis Hayes

They're doing what they feel, and if they're doing what they feel, they're doing what they should do. Because if they don't do what you feel, then you're telling a lie. You can do downtown and hear some good Dixieland. And you can listen to Cecil Taylor if you want, and you can go listen to Miles, Charlie Mingus, Lennie Tristano... Everyone should realize his station, and everybody should man their stations. That's all.

Jackie McLean, Downbeat 1963

Jackie McLean & Co. (1957) signed by Jackie, Mal Waldron

Activist, alto saxophonist, arranger, band leader, composer, educator, and ex-junkie, Jackie McLean lived a rich and full musical life. Born in New York City and raised in the famed Sugar Hill section of Harlem - the home of Cab Calloway, Nat King Cole, Duke Ellington, and Thurgood Marshall - Jackie grew up surrounded by music. His father, John, played guitar in Tiny Bradshaw's orchestra, though he died when Jackie was only eight years old, and Jackie's step father, Johnny Briggs, was a record store owner where Jackie worked as a kid. So Jackie Mac was probably digging in crates long before it became my personal obsession and a YouTube series phenomenon!

Strange Blues (1957) signed by Jackie

From his 1951 recording debut on Miles Davis' Dig to the more than fifty records he released as a leader and the hundreds he participated on as a session sideman, Jackie McLean was an immense jazz figure and influence. Jackie's early tutoring was also enhanced by his Sugar Hill neighbors, Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, and especially Bud Powell. Jackie recalled visiting with Bud in his apartment, after being introduced by his brother Richie whom he met in the record store, "Bud was the most significant person in terms of my development in my early years. The time I spent hanging around his house between fifteen and seventeen were very important, formative years for me. I think my growth and development happened because I was in his presence. A lot of people have the idea he was giving me theory lessons. That wasn’t it at all. I heard him practice a lot, play a lot. He also let me take my horn out and play along with him. He taught me some things he was writing, kind of coached me along."

Bird Feathers (1957) signed by Jackie, Phil Woods

Such kindness and generosity was instrumental in developing Jackie's growth as a player and composer. It is even more remarkable, considering Jackie didn't pick up a saxophone until he was fourteen years old and a scant five years later, Miles Davis and Sonny Rollins recorded "Dig" with Jackie contributing a hard blowing alto saxophone. Jackie later remembered the circumstances of only the second composition he ever wrote, " And then I wrote “Dig” when I was about 17 and a half or 18. That’s when I went down to the Birdland and sat in with Miles, and then went to his house the next day. And he had asked me if I had any tunes and I told him yes, and I played “Dig” for him, and right away he said, 'Oh, show me that.' ...and I played it for him, and we played it together. And then I started working with him, and I started learning his repertoire.”Heady stuff for a teenager, Jackie's renown and acclaim was just beginning, "One night , Miles told me to come down when he was working with Coleman Hawkins in Birdland. Miles said, 'Come on down tonight, I want you to check out something.' I went down, and I looked up, and when Miles saw me come in and sit at a table, he whispered something to Coleman Hawkins. And he counted off, and I saw Coleman Hawkins play “Dig” with Miles."

2 Trumpets (1958) signed by Jackie, Barry Harris, Donald Byrd, Art Farmer

Such promise was almost completely derailed by his rapacious addiction to heroin. Like many jazz artists enraptured by the wizardry of Charlie Parker, Jackie fell prey to following his insidious pursuit of drugs. As Jackie recalled, "A lot of guys in my community that idolized and worshipped Charlie Parker began to experiment." As the drugs began to exact their unrelenting toll, Charlie counseled Jackie, "You know, Jackie, man you should try to be like Horace Silver and some of the younger musicians that's coming along today, and get yourself together...I feel responsible for what you're doing, and you need to come on and kick me in the behind for this, you know?"

One Step Beyond (1963) signed by Jackie

Unfortunately, Charlie's advice went unheeded, Jackie's addiction was in full bloom, "When I was strung out on dope, my horn was in the pawn shop most of the time, and I was a most confused and troublesome young man. I was constantly on the street, in jail, or in a hospital kicking a habit…. The New York police had snatched my cabaret card and I couldn’t work the clubs any more except with [Charles] Mingus who used to hire me under an assumed name." Fortunately, the recording studios did not require a cabaret card, so Jackie was able to record, and he was quite prolific during the 1950s, notwithstanding his perilous afflictions.

The Connection (1960) signed by Jackie

Looking at new avenues for artistic expression, Jackie performed in The Connection in 1959, an Off Broadway play by Jack Gelber (later a record and a movie) which was breaking new ground in the theater. The premise was four or five musicians sitting around their apartment, waiting for their dealer to come. Actors were placed in the theater (including an uncredited nineteen year old Martin Sheen!) to serve as a catalyst to audience participation, and the jazz musicians could really lay out and improvise freely on the music, written by jazz pianist Freddie Redd, also a cast member. Not the standard theater fare circa 1959, to be sure. The Living Theater play, had an almost four year run, starting in New York City, then performances in London in 1960, Los Angeles in 1961, and a European tour in 1962. It had a lasting effect on Jackie, "It made me watch actors go through their creative thing every night. I compared it to playing jazz... I fell in love with theater then and there. Even my saxophone playing became a lot more theatrical after that." Jackie described the final performance, "The show went five hours because the tunes were so long. And I took the regular tunes we played - "A Night In Tunisia", "Tune Up" - and instead of playing chorus after chorus of straight changes, when I felt it, I went 'out to lunch.' The audience felt it too, I believe they did." Yes, the nascent influence of 'free jazz', the complex and challenging music of Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy and Cecil Taylor, was being absorbed by Jackie. As Jackie noted in his 1963 liner notes to Let Freedom Ring, "Ornette Coleman has made me stop and think. He has stood up under much criticism, yet he never gives up his cause, freedom of expression. The search is on."

Perhaps, the greatest achievement of the play was Jackie's ability to break his nearly eighteen year heroin addiction in 1964, a year or so after the play closed. I'm sure four years of living and breathing the play had an effect, subliminal or otherwise. Almost immediately, Jackie began to give back, going to prisons and helping as a drug counselor. There is nothing more credible or effective than one recovering addict talking with another. They speak the same language, they live the same life, they tell the same lies.

Destination… (1963) signed by Jackie, Roy Haynes

As rock music began to eclipse jazz in the mid to late 1960s, Jackie took a gig in 1968 at the Hartt School of Music in Hartford, Connecticut as an instructor. "When I arrived at the Hartt School of Music to teach a history course, I said 'Look, I don’t know anything about anything except what I experienced.' And I talked to other musicians, they said 'Well, that’s what they’re hiring you for, man. They don’t expect you to talk about ragtime and all that.. go with what you know. Build a course around your experiences.' So that’s what I did in the beginning." From those modest beginnings, Jackie would build a curriculum that focused on African American Jazz Studies, probably the first of its kind at any university in the United States. Nearly fifty years later, The Jackie McLean Institute Of Jazz (renamed in tribute to Jackie in 2000 - so long African American Music Department, hello Jackie Mac!) is a thriving program and one of the nation's preeminent, offering a Bachelor of Music Degree in Jazz Studies.

Hard Cookin’ (1965) signed by Jackie, Ray Bryant, Frank Foster

I saw Jackie perform in jazz clubs in New York City over the years, and his tone was so distinct, a searing and mournful pierce that made me sit up straight in my seat. His playing was fast and brilliant when needed, and drenched in soulful blues which he knew only too well. Jacckie usually had his students perform with him, many of whom have gone on to release acclaimed jazz records, like trombonist Steve Davis and saxophonist Jimmy Greene. Jackie once explained why he enjoyed playing with his students, " It would be much easier for me to get five experienced musicians: Billy Higgins, Cedar Walton...go out and play. Then I wouldn't have any worries about what might go right or what could happen. But I like young musicians because they make mistakes and they cause things to happen on the stage. And then we straighten it out and we keep moving forward, and at the same time, little new things slip in here and there through these encounters."

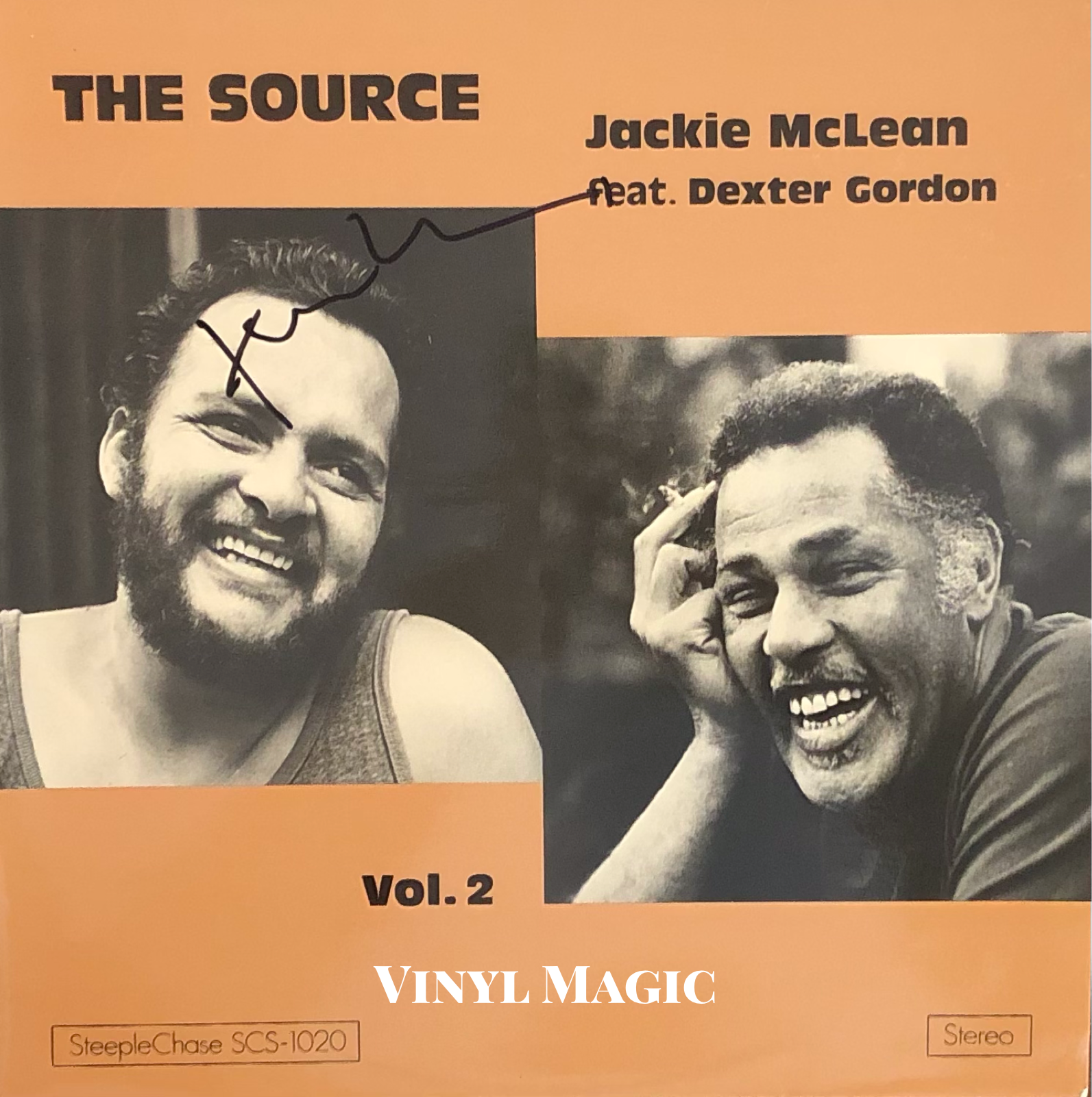

The Source Vol. 2 (1974) signed by Jackie

Off stage, Jackie was generous and surrounded by well wishers who were thrilled to be in the presence of Jazz royalty. Since he had so many responsibilities at school, Jackie toured infrequently in the 1990s. So when Professor McLean took the stage, hard bop was in session and the audience was gripped in rapt attention. When signing the vinyl after the shows, Jackie enjoyed looking at the covers, reminiscing of a young man finding his art, despite his early struggles. Jackie's warmth and humility radiated.

It’s About Time (1985) signed by Jackie, McCoy Tyner, Al Foster

In a 2000 interview, Jackie revealed, "I'm always hearing music. It's like you have a turntable or a CD player in your head. So when you ask, who is the real Jackie McLean? I have to say I'm a struggling saxophone player - a player who's struggling to play the instrument to the highest level that I think I was meant to play."

Jackie McLean overcame his struggles mightily, and the world of education and jazz is far richer.

Shout out to my great friend Larry Y. who attended classes with Professor Jackie Mac in the mid-80s. I only wish he had the tapes!

New York Calling (1975) signed by Jackie

Choice Jackie Mac Cuts (per BKs request)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JelFK12ACGg

“Dig" Jackie, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins 1951

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1mwEwzvXTPs

"Bluesnik" Bluesnik with Freddie Hubbard 1961

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ia7fxLqJKjY

“When I Fall In Love" 4, 5, and 6 1956

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_soxsh3zwMQ

"Cool Struttin' " Jackie McLean Quintet Live 1986

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z2fry_Axh_Y&list=RDZ2fry_Axh_Y&t=24

"Little Melonae" The New Tradition 1955

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RY6mtjvNti4

"Soul" Soul 1968

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y5lXtN5_Jqc&list=RDZ2fry_Axh_Y&index=3

“Dr. Jackle" Miles Davis & Milt Jackson with Jackie Mac 1955

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5qUhlm7uNSY

"Dr. Jackyll and Mister Funk" Who says hard bop can't hard funk? Jackie Mac and friends 1979

Bonus track:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9UP10CYIdEE&list=RD9UP10CYIdEE&t=216

"Crate Diggers with DJ Jazzy Jeff"

Action (1964) signed by Cecil McBee, Charles Tolliver