Ray Brown and Me…

I was around music all the time. And my father liked Fats Waller so much that when my folks gave parties, he hired a guy who looked like Fats Waller, who played very little piano, he sang a little bit, but he wore tails and a top hat just like Fats Waller, and my father would tell all the guests, “After you get a few drinks, he sounds real good.” This guy would imitate Fats Waller, singing “Your Feet’s Too Big,” sang all those songs, and he played the piano. My father couldn’t get Fats Waller, but that was the best thing he could do. So there was music all the time in my house.

Ray Brown

The Duke Ellington Songbook signed by Ray, Oscar Peterson, Ed Thigpen

Ray gave me confidence. I never had to wonder and worry about where things were going harmonically or rhythmically. He listened to each performance that everyone gave, and adjusted his playing to you on different nights, which not a lot of bassists do. He would walk different lines behind me, change the harmonic pattern, just to see what I would do.

Oscar Peterson

Jam Session #1 (1952) signed by Ray, Benny Carter, Oscar Peterson

Like nothing I’ve ever heard before. They played tempos and keys and songs that I had never heard of, and you’re just standing there watching and trying to keep up. Dizzy and Charlie Parker played so good, it was a frightening experience.

Ray on playing with Bird and Diz

Way Out West (1957) signed by Ray, Sonny Rollins

Ray Brown was a continuous circle of beyond normal. There was nothing on the planet… and I’m not just saying it out of emotion and sentiment. In my opinion, what he stood for, just when he laid that rhythm down, it was like…a Mack Truck with a Rolls-Royce engine. That’s what it was. To me, the last times I played with him, every time from the beginning, there was that sense of excitement that I would get, that I’m playing with this guy who is like a royal duke. He’s a King. He’s not a normal level of bass player. He had something in him that was brilliant, just brilliant.

pianist Monty Alexander

Something For Lester (1978) signed by Ray, Elvin Jones, Cedar Walton

Ray Brown was arguably the very first bass player to revolutionize note lengths. Most bass players before Ray Brown played very short, choppy notes, and Ray Brown revolutionized the sound of the bass in that his notes were very long. Every note got its full value. A quarter note was actually a quarter note. A half note was actually a half note. A whole note was actually a whole note. How Ray Brown came across playing that way during a time when nobody did, it will always be beyond me, but I guess being in the company of Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker and Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk and Kenny Clarke and Max Roach, and the man who I’m with now, Roy Haynes, I’m sure greatness and innovative ideas would run rampant.

bassist Christian McBride

We Get Requests (1964) signed by Ray, Oscar Peterson, Ed Thigpen

One of my favorite albums (of any genre) is Duke Ellington's This One's For Blanton, a duet with Ray Brown and a tribute to Jimmy Blanton. Jimmy revolutionized the bass as a leading instrument in jazz with the Duke Ellington Orchestra in the late 1930s-early 1940s before succumbing to tuberculosis at age twenty-three.

This One’s For Blanton (1973) signed by Ray

Ray remembered seeing Blanton perform when he was still a teenager in Pittsburgh, "The problems with the bass back in 1940-41, which is when Blanton was very prominent (or any other bass player), there were no amplifiers. There was a microphone in front of the band, and the saxophone player came up and played solos off it, the singers sang, and the leader would make announcements on it. I mean, there was just one microphone up there. Until Duke Ellington showed up and had a special mike on Jimmy Blanton standing in front of the band, you never heard the bass that well. I mean, you heard the guy playing, but you couldn’t do anything fast on bass because nobody would be able to hear it. So Blanton was an oddity in the first place, and a lot of people didn’t understand it...he just changed it. From black to white, that big a change. Just picking it up, he was different. I mean, he had the best sound you ever heard. He played the best lines, he played the best solos. He did everything! And everybody was into Jimmy Blanton."

Memphis Jackson (1970) signed by Ray, Milt, Harry Sweets Edison, Harold Land, Teddy Edwards, Ernie Watts

Of the 1973 recording with Duke Ellington, Ray said, "Well, I made maybe half a dozen sessions with Ellington, whom I had always wanted to play with ever since I was knee-high to a duck. But Norman Granz said to me, "You and Duke ought to do some things like he and Blanton did." I said, 'Oh, I don't know about that. Well... let's talk about it.' He tried for years to get us together, we were just in different places all the time. Duke was busy and he was someplace, and I was busy someplace. Of course, this was the last record he made before he passed, and I was fortunate to get in the studio with him. The second session we did, he was pretty sick. He had a fever, but he came in and played magnificently.”

Oscar Peterson Trio+One (1964) signed by Ray, Oscar, Clark Terry, Ed Thigpen

Revered as a composer and terribly underrated as a pianist, Duke Ellington played magnificently, but the anchor was Ray Brown's deep, resonant bass, each thump and thwack meticulously played, coursing each note and rhythm deep into the soul. A master class in piano and bass by two master musicians, This One's For Blanton is a glorious denouement, a fitting last bequest in Ellington's unparalleled career.

Much In Common (1964) signed by Ray, Milt, Kenny Burrell, Jimmy Heath, Albert Tootie Heath, Hank Jones

The education and introduction of the greatest bassist in Jazz history (with apologies to Jimmy Blanton, Ron Carter, Charles Mingus et al.) was rather haphazard and unplanned. Ray explained, "Well, it was very simple. I went to junior high school, and I signed up for orchestra, and they had about... 28 piano players and they had 3 basses and only 2 bass players. So every day, there was a bass laying on the floor, doing nothing. And I’m sitting over there waiting for my 15 minutes a week to sit down to the piano. It’s difficult for teenagers to sit around all day and not do anything and stay out of trouble. So I asked the teacher,'Hey, if I was playing that bass, I could play every day.' He said, “That’s right. We’re looking for another bass player.” I said, 'Okay, you’ve got one.' And that was it."

Swinging Brass signed by Ray, Oscar Peterson, Ed Thigpen

Ray went on to play with everyone from Louis Armstrong to Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker to Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holiday to Ella Fitzgerald. Ray and Ella were even married for six years, until the rigorous demands of their peripatetic schedules forced an amicable dissolution. Although the marriage was over, their professional relationship continued as Ray was in demand as the top bassist for studio sessions. In his indefatigable career, Ray released more than sixty-five records as a leader/co-leader, appeared on two-thousand more as a side man, and was acclaimed for his brilliant work and long tenure with the Oscar Peterson Trio from 1951-1966.

Just The Way It Had To Be (1970) signed by Ray, Milt, Monty Alexander,, Teddy Edwards

In 1966, Ray relocated to Los Angeles, and backed Tony Bennett, Frank Sinatra, Sarah Vaughan, and a young Quincy Jones. Ray was already developing a reputation as a shrewd businessman and negotiator and he was also managing The Modern Jazz Quartet. Quincy recalled their evolving friendship, "After he moved to Los Angeles, we started working a lot together. We got closer and closer. After a while, Ray started to take care of booking gigs and travel. He was an astute businessman. Old school played everything. We all played chitlin’ circuits, and you didn’t sit around whining about what you had to play, man. You played it, and tried to make it all sound good. That’s what I loved about Ray. That’s where I think our chord struck, in being very curious about what the business side of it was and not wanting to be a victim. We wanted to be more in charge of our own destinies." Ray's business acumen remained resolute, as Ray took responsibility for booking his own engagements and all aspects of his recording and performing career. By all accounts, he was a tough and skilled businessman who did not suffer fools.

That’s The Way It Is (1969) signed by Ray, Milt, Teddy Edwards

Ray also did studio work with music avatars B.B. King, Elvis Costello, Linda Ronstadt and Steely Dan, and Ray was instrumental in bringing a young Diana Krall to Los Angeles in the early 1980s after seeing her perform in a restaurant in her native British Columbia. Diana was strictly an instrumentalist then, and Ray was impressed with her piano chops.

Reunion Blues (1971) signed by Ray, Milt, Oscar Peterson, Louis Hayes

I saw Ray perform more than a dozen times through the years, mostly at clubs in New York City, like the Blue Note and Birdland. Ray always had great musicians with him on the bandstand, a mix of younger stars like pianist Benny Green, bassist Christian McBride, and drummer Karriem Riggins, along with established legends like Milt Jackson, Oscar Peterson and Monty Alexander. Warm and polished on stage, Ray could be gruff and dismissive off stage. Several times, I asked him to sign one or two albums, and he replied with a curt, "Not now." I knew I had to be patient if I were to effectively stalk my prey, so I would wait and eventually get one or two signed by Ray, albeit begrudgingly.

Montreux ‘77 (1977) signed by Ray, Milt, Clark Terry, Monty Alexander

It all changed one night when Milt Jackson, Oscar Peterson, Karriem Riggins and Ray played a gig at the Blue Note in November, 1998. They were recording a live album, a reprise of the Very Tall Quartet, an album originally released in 1961. By this time, I had become good friends with Sonny, Milt Jackson's brother-in-law, tour manager and erstwhile bag man. After seeing Milt so many times (and Milt signing so much vinyl), Sonny greeted me as an old friend. I asked him, "What's up with Ray? He's always difficult. Can you hook me up with some signatures?" Sonny smiled broadly, "That's Ray. That's why we call him 'Hog.' You wanna know why?" I had no idea, I shook my head, 'No.' "We call him 'Hog' because he wants to hog all the booze, all the drugs, and all the women. That's why he's the 'Hog' ", Sonny offered brightly. 'Well, let's go see 'Hog', only I ain't calling him that,' I replied. "No, you best not. Let's go," and I followed Sonny as he led me to Ray's dressing room. As we entered, Sonny said, "Ray, this is a good friend of mine. He's a big fan, can you please sign some vinyl?" A big smile radiated from Ray, like he was digging into a meaty, greasy twelve-bar blues on stage. "Yes, I'd be happy to. What ya got?" I handed him a bunch of vinyl and Ray was as happy and effusive as I had ever seen him. Offstage.

Ray Brown, a brilliant if mercurial musician and composer. And the best bass player ever.

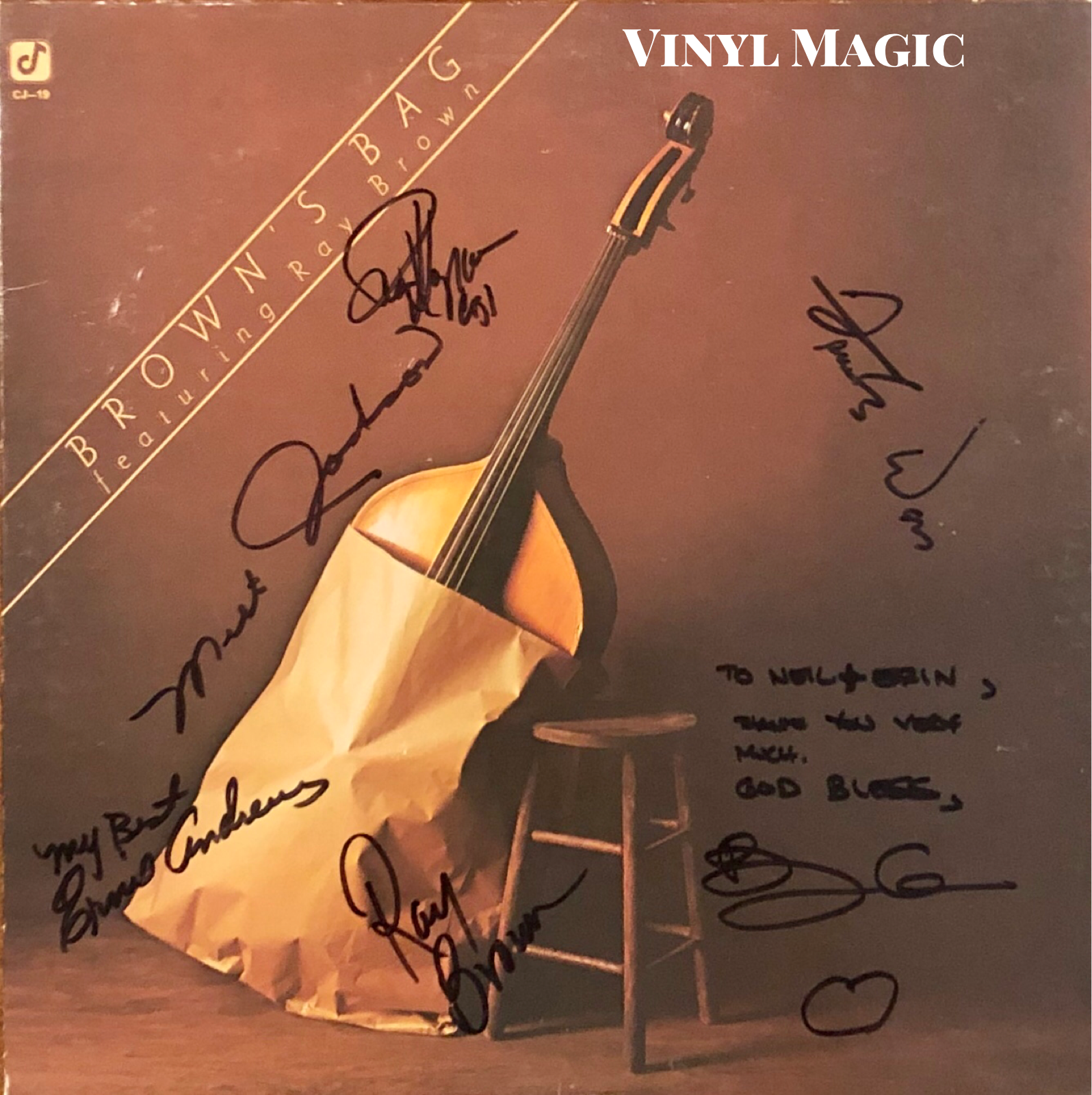

Brown’s Bag (1976) signed by Ray,, Milt, Ernie Andrews, Benny Green, Karriem Riggins, Frank Wess

Jones-Brown-Smith (1976) signed by Ray, Hank Jones

Soul Route (1984) signed by Ray, Milt, Gene Harris, Mickey Roker

Choice Ray Brown Cuts (per BK's request)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KS6UJgdEDjs

"Do Nothing Till You Hear From Me" Duke and Ray This One's For Blanton 1973

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xyDCwWAbVcU

"Things Ain't What They Used To Be" Duke and Ray This One's For Blanton 1973

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NTJhHn-TuDY

"C Jam Blues" Oscar Peterson, Ray Brown, Ed Thigpen live in Denmark 1964

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tCrrZ1NnCuM

"Hymn To Freedom" Oscar Peterson, Ray Brown, Ed Thigpen live in Denmark 1964

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rYWHMFe1kFc

"Blue Monk" Live with Benny Green, piano, Greg Hutchison, drums

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o3T_gHWXyt4

"Take The 'A' Train" Live with Gene Harris, piano, Grady Tate, drums 1985

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2l5CHNypezY

"I Want To Be Unhappy" Live with Monty Alexander, piano Herb Ellis, guitar 1988

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oL4vhji_n3c

"Meet The Flintstones" Triple Scoop Ray with Monty Alexander, piano Herb Ellis, guitar 1982

Jackson, Johnson, Brown & Company (1983) signed by Ray, Milt, J. J. Johnson

Quadrant (1977) signed by Ray, Milt, Mickey Roker

All Too Soon (1980) signed by Ray, Milt, Mickey Roker

The Big 3 (1975) signed by Ray, Milt

Diz And Getz (1986 reissue) signed by Ray, Dizzy Gillespie, Herb Ellis, John Lewis, Max Roach